Video by Eliav Gabay

Article by Jeff Metcalfe

For years now, two arrows protrude near the base of a small cactus in the backyard of Charlie Johnson’s north Phoenix home.

He could remove them any time, but they serve a purpose. To remind him of his early attempts at archery, a sport he took up in his early 90s and has considerably improved at with age. Johnson turned 102 in June, four months after competing for the first time at the prestigious Vegas Shoot, an indoor tournament dating to 1962 that has grown to a 4,000-archer competition.

Kris Schaff took home a $57,000 first prize for winning the championship compound division in Las Vegas. But arguably the three-day event’s star attraction was Johnson, finally talked into participating by archery coaches Kevin Ikegami and Dick Tone and his wife, Bonnie McCulley.

“I’m not going there, these guys are professionals, and I don’t know anything about it,” Johnson recalls saying. “Next thing I know my wife had booked a hotel so when it was time to go, I went. That was the time of my life. It was just fantastic. They were treating me like I was a professional.”

Johnson is actually an unlikely amateur to even be in the sport given his late start – “I wish I started when I was nine,” he said during an interview in Vegas – or even to still be living. There are close to 100,000 U.S. centenarians (100 or older), still just .0002 percent of the total population.

Johnson could be one in 340 million Americans when combining his age and archery.

“Even discounting archery, it’s amazing to get to see and talk to this person who is 102,” says Ikegami, President of the Papago Archery Association. “He’s still passionate about everything. His independence is incredible. You can’t help but have a huge grin on your face around Charlie. He’s what everyone would strive for.”

Overcoming segregation

Growing up in then segregated Clarksburg, West Va., in the 1920’s and ‘30s, archery and painting – his other late-life pursuit – were nowhere on his radar.

Johnson lived in an Italian area at the bottom of a hill. His mother Evie and maternal grandmother Fannie, born into slavery in 1861, raised Charlie, his brother and two sons by Evie’s sister.

Stay away from the top of the hill, Fannie reminded Charlie one night after he and his brother came home talking about people burning crosses.

Italian and Black children could play together in the neighborhood but it was different uptown. “We didn’t even speak to each other,” Johnson says. “We weren’t allowed to do that. We’d go to the movies, we had to go upstairs. You’re not allowed to love each other. I couldn’t understand it.”

“You’d better not look at a white girl,” ironic now since his second wife Bonnie is white, symbolic of him living long enough to see significant racial progress.

“My kids love him, his kids love me,” Bonnie says. “We’ve never had any (racial) problems. Partly because he doesn’t have a bone to pick. Let’s just have harmony and love and I care for you as a person. He’s comfortable in his skin, which helps you to be comfortable.”

Johnson’s earliest aspiration was to be a coal miner – “They kept pockets full of money,” he says – his mother insisted on Charlie becoming the first male in the family to graduate from high school. He achieved that goal in 1939 then attended trade school through the National Youth Administration program before starting miliary service in 1942, four days after marrying his first wife, Effie.

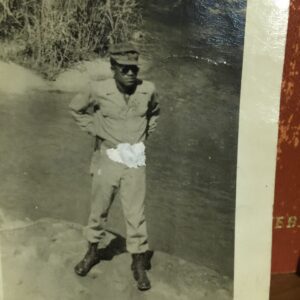

Johnson’s Army career included two years in the Pacific, mostly the Philippines, during World War II under the command of Gen. Douglas MacArthur. He supervised trucks that were part of the Highway Transportation Division’s Red Ball Express, vital for keeping troops supplied.

“I was getting ready to go to Japan when they dropped the (nuclear) bomb,” Johnson says. “So instead I came home,” in December 1945, discharged on his oldest child’s birthday. She soon will turn 80.

Finding his post-WWII calling

Coal mining no longer appealed to Johnson after the war.

Instead, he settled his family, which would grow to include five children, in Ohio and for a decade drove a Cleveland city bus. Then he became a barber, with a shop in the Glenville area near where rioting broke out in 1968 after a shootout between police and Black nationalists.

“I knew everything in the community,” Johnson says. “My wife had a beauty shop next door. She knew what happened with the women and I knew what happened with their husbands. A lot of times, we were mediators between the two.”

That amateur counseling grew into Johnson’s life calling.

After becoming a Catholic and eventually a deacon in the church, he opened a small store to assist those in need in the Black community.

“It got too big for that so they said we’ve got to build you another one,” Johnson says. “The bishop gave me a million dollars and said you have to beg the rest. So we built the center at about $3 million,” raising additional funds from steel companies and a federal grant.

“The bishop told me my task was to take care of the old folks, the children and the needy. That was my sole purpose.”

The St. Martin de Porres Family Center today annually assists 2,000 low-income families through an array of programs designed for all ages. It is named after Johnson’s patron saint, a 17th century Black lay brother from Peru who was canonized as a saint in 1962.

Johnson left as the center’s director for a new ministry as a hospital chaplain, first in Ohio then Missouri and Arizona as his second wife (after Effie’s death) took hospital ministry jobs.

Charlie is 30 years older than Bonnie. They met in chaplaincy school when he was 67. “People are saying you aren’t going to be together long,” Johnson says. “Bonnie said we’re going to try it for five years.”

They married in 2000 and are completing their seventh five-year trial since meeting 12 years earlier.

Bonnie was in awe of the reception for her husband in Las Vegas and of him daily.

“That’s what he teaches me, how to inspire people, how to love people,” she says. “I’m overwhelmed how people in archery especially care. At the Papago tournament, all the young kids will come up and give him a hug. That’s what they highlighted at Vegas – the 9-year-old and the 102-year-old. You can all do this.”

What is it about Charlie that makes him special, even Bonnie wonders. “Is it the energy, does it come from the soul? I think it does because people are drawn to him. It’s the love in his heart.”

Aiming for improvement

For most of the last 15 years, other than four in Oregon, Johnson has been an Arizonan.

He began shooting archery at the Papago range because that’s what three of his Monday/Friday golfing buddies did on Wednesday. “I got hung on it,” he says, continuing in Oregon where his technique improved.

Tone, who coached 1988 Olympic gold medalist Jay Barrs and was 1992 U.S. Olympic team coach, and Ikegami became more involved with Johnson upon his return from Oregon. They arranged for Hoyt to gift Johnson with a $2,000 target bow for his 100th birthday.

“He has a pretty heavy bow and still uses a stabilizer,” increasing the weight, Ikegami says. “It’s a 35- to 40-pound draw. He shoots 1-2 hours (practice) and he’s not doing it passively. He’s talking about what he’s focused on and his form. It’s lots of walking (retrieving arrows). I’ve never heard him complain once.”

Johnson still drives, cautiously, 18 miles to the range when his friend Mike Gartland isn’t available. For those close to him, the challenge is to protect him without bubble wrapping his independence. He expects this to be his final year of driving because of peripheral vision issues.

Still bench pressing 220 pounds into his early 70s, Johnson has slowed down in the ensuing three decades. He has knee issues, suffering occasional falls, and hearing problems going back to teaching on Army rifle range. “I can still read very well,” he says. “My wife writes a lot for me. It takes me time to do it.”

“People ask me how does it feel to be 100. I don’t know. I’ve never been here before. Sometimes I get shamed around people that are crippled, to say I’m 102. These people are old and lived good lives and accidentally or because of their age can’t do things.”

Johnson began painting in 1994 and has landscapes he doesn’t give away hang throughout his home. Bonnie fuels his inner Bob Ross and won’t take no for an answer when it comes to traveling. “Since we met, I’ve been almost everywhere,” he says. “She’s been a plus for me. Before that I had only been out of the state in the Army.”

“If he wasn’t out there, he’d be dying inside,” Bonnie says. “He’d start failing. We thrive when we do the right things that give us energy and purpose.”

On the trip to Las Vegas, Johnson finished ahead of two archers in his compound flight and all but two in the flight below his. It’s tick tock of his heart rather than TikTok that matters for Johnson, but he was something of a viral sensation on site at South Point Hotel especially with fellow military veterans, none but him from World War II.

“It was like Bono walking through,” Ikegami says. “He has actually improved, which is incredible. He doesn’t take his age into consideration at all. Naturally all the rest of us do. I tell him you showed up, you already won, but he’s always trying to push himself.”

Johnson, smartly, doesn’t often get ahead of himself, just living for today, but wants to return to the Vegas Shoot, if nothing else to perform better.

“To be able to pull that arrow back and shoot it, it just does something to you whether you hit the target or not. You know you can get better,” he says. “This is the first time I ever told people I will see you next year.”